I wanted to take a closer look at Cipe Pineles because I feel like her work is extremely interesting and pretty brilliant. I feel like her name is kind of forgotten by people (including myself), but her work – well, everyone knows it. I wanted to dig deeper into her life and her influences and how she got her start.

Born in Austria in 1908, Cipe Pineles would be one of the most influential women of graphic design and art direction during her time. After graduating from Pratt University, Pineles was offered a job at Contempora Ltd (Condé Nast publications), right out of school, where Condé Montrose Nast himself (founder and publisher of other magazines like Vogue, Vanity Fair, and The New Yorker) saw great potential in her. By the 1930s, Nast got Pineles jobs at Vogue and Vanity Fair, where she learned editorial direction first-hand from M.F. (Mehemed Fehmy) Agha, the art director of Vogue, Vanity Fair, and House and Garden. By 1943, she got her start in New York as the first woman art director of Glamour magazine – a “mass-market American publication.” Pineles would continue her big career as art director of magazines like Seventeen, and Charm. She would continue to put her mark on these big magazines.

Below are a couple of designs done by M.F. Agha for Vogue magazine in 1932. Although he has a completely different approach to his designs (more illustrative), you can see the influence he had on Pineles. As a result of overseeing and working directly with Agha, Pineles picked up on his minimal, simplistic, and clean approach to design.

While Pineles was learning the ins and outs of graphic design and editorial design from Agha, she worked on several covers for Vogue. She was given a lot of freedom while working there because they didn’t have a logo. Agha encouraged his workers to experiment with things and find something that spoke to them, something that they were good at. Pineles found that she was interested in photography and she was exceptional at it. It was actually perfect, too, because photography took the place of fashion illustrations – so her talent was wanted…and pretty much essential at this time. Agha forced Pineles to be the best she could be. Pineles says: “Agha was the most fabulous boss to work for. Nothing you did satisfied him. He was always sending you back to outdo yourself, to go deeper into the subject.”

WIth the help and preparation of Agha, Pineles became art director of Glamour magazine in 1942. Pineles had some of the best photographers (Andre Kertesz, Herbert Matter, Cornell Capa, Toni Frissel, and Trude Fleischmann) and several designers and artists of that time work with her to make it that much better.

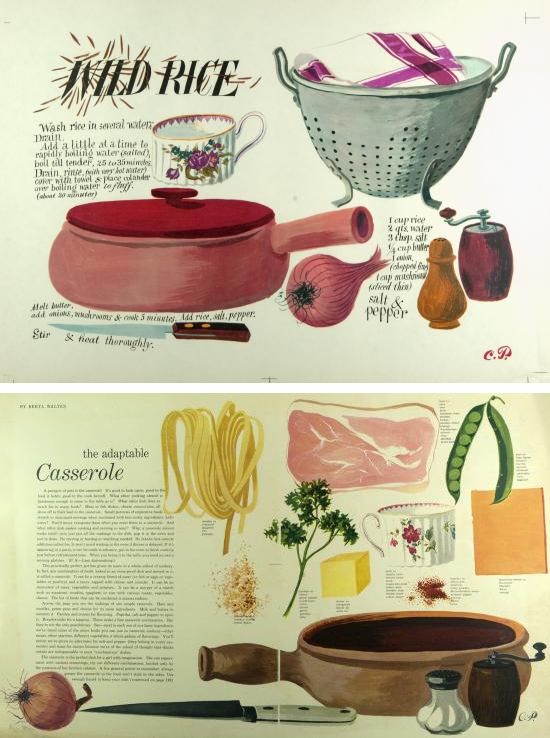

During the time of World War II, Pineles began working as the art director of Seventeen magazine, which had only been around for three years prior. Very much like today, the audience of the magazine was teenage girls. The founder and editor of the magazine, Helen Valentine, didn’t want the magazine geared toward “silly, only-marriage-minded girls,” she wanted it directed toward “serious and intelligent young adults.” As a result, Pineles moved the magazine in a different direction. She had some of the best illustrators (including herself) bring different things to the attention and interest of the young public like food, household items, furniture, etc. She also brought more playful typography and visual puns to her designs.

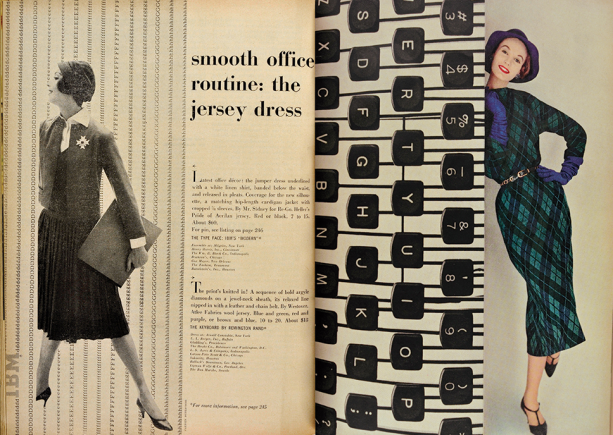

In 1950, Pineles left Seventeen to go to Charm magazine. The magazine was geared toward the working woman and had pages on knowledge, money, and their futures – and of course the usual beauty and fashion concerns that women had. While still addressing these things, Pineles also made sure to include the values of women as well as the changing roles in men and women (at home and in the workforce). One of the main focuses of the magazine was on fashion for the working women (at the office, commuting, lunch-hour shopping, etc).

Pineles went on to work as an art director for Mademoiselle and in 1961, she became an independent consultant designer and teacher of design. Pineles taught editorial design at Parsons School of Design up until the mid 1980s. She taught her students how to become successful art directors and gave them “real world” projects to prepare them for the editorial world. Up until Pineles retired and later passed in 1991, she had received countless awards and had been inducted into the Art Directors Hall of Fame.

I find Pineles’ work – and her direction in art – so fascinating. Her work changed so much over the course of twenty years (or more). Being a graphic designer myself, I find it really interesting how she’s been in the public eye (and their actual hands) for so long. I feel like she had such a big impact on editorial design and brought a completely different side to it – that was never really seen before…and hasn’t really been seen today.

Sources:

“Cipe Pineles.” The American Institute of Graphic Arts. 1998. Web. 4 April 2014. <http://www.aiga.org/medalist-cipepineles/>.

“20th Century Editorial Design: Cipe Pineles.” RIT Graphic Design Archive Online. Web. 4 April 2014. <http://library.rit.edu/gda/designer/cipe-pineles>.

“Badass Lady Creatives [In History]: Cipe Pineles.” Designworklife. Web. 4 April 2014. <http://www.designworklife.com/2014/01/22/cipe-pineles/>.

Meggs, Philip B. “Megg’s history of graphic design.” The New York School. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012. Print.